Editors Note: This post also appears on humanitariandisarmament.org’s Disarmament Dialogue blog.

Twenty years ago, on May 12, 2003, I crossed a US Navy-built bridge into southern Baghdad and a world most people knew only from TV coverage. The capital city had fallen about a month earlier to US forces, and I was part of a three-person Human Rights Watch team sent to document civilian casualties from the hostilities.

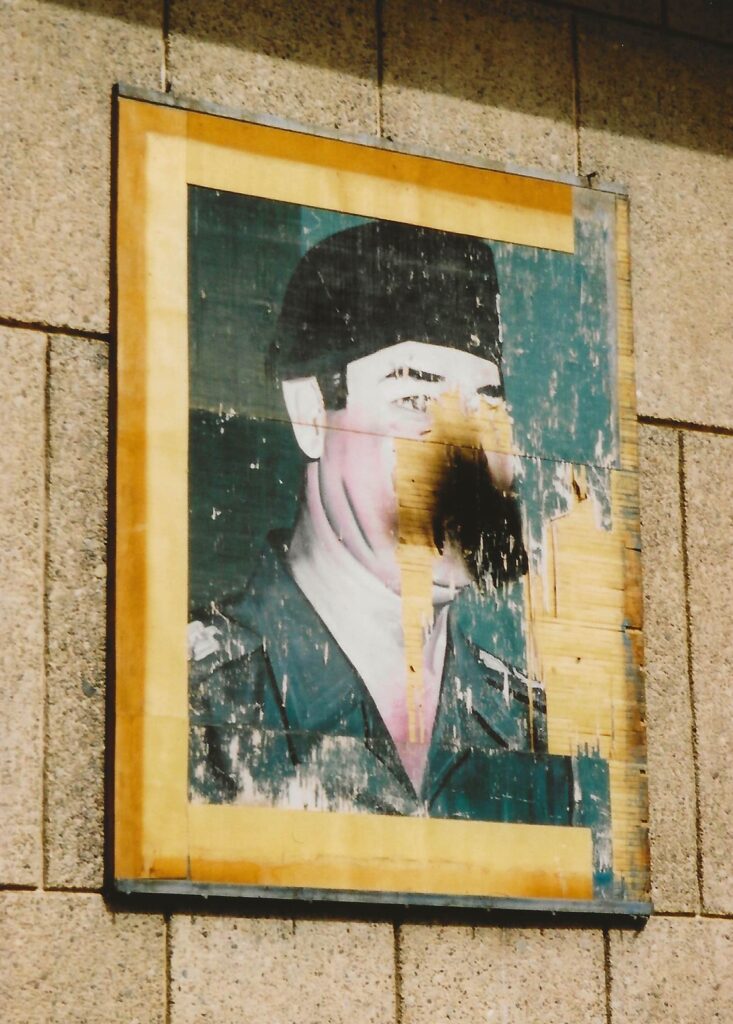

Over the ensuing days, I saw evidence of fighting and the recent regime change lining the roads. Abandoned tanks stood amid palm trees and homes. Government buildings reduced to rubble served as reminders of the US-led coalition’s “shock-and-awe” campaign. Statues, murals, and other images of Saddam Hussein were omnipresent, but they had been defaced since the dictator’s fall.

While we did not fully anticipate the extent and nature of the violence that would wreak havoc on Iraq for years to come, it was clear then that the war was not over. From our vantage point on the roof of the Hamra Hotel, a base for journalists and aid workers, we could still hear gunshots and see tracer fire over the skyline.

We conducted our investigation in Baghdad and the major cities to its south, including al-Hilla, al-Najaf, al-Nasiriyya, Basra, and Karbala’. Through interviews and analysis of physical evidence, we documented extensive civilian casualties caused by the coalition’s use of cluster munitions and failed US air strikes on Iraqi leaders. We also recorded Iraqi violations of international humanitarian law, such as the use of human shields and abuse of the Red Cross and Red Crescent emblem. In December 2003, we published our conclusions in a major Human Rights Watch report entitled Off Target: The Conduct of the War and Civilian Casualties in Iraq.

During the course of our fact-finding mission, I bore witness to a significant moment in history while thinking about our project in a larger context of how humanitarian crisis and conflict is reported.

I remember visiting famous landmarks that were emblematic of the time: the mosque near the Palestine Hotel that appeared as the backdrop of so many reporters’ broadcasts; the palace with monumental heads of Saddam as Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar, which had become headquarters of the coalition’s Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance; ancient Babylon with US Marines touring the site.

I also recall encounters with individual Iraqis whose varied perspectives reflected the complexity of the conflict. At our hotel one evening, our interpreter flipped slowly through the deck of cards the US military had produced of wanted Iraqi leaders and told me the story of his brother’s disappearance and his family’s failed attempt to find him. At a mass grave, a wailing mother clung to an unrecognizable body and told us she was convinced it was her son because she found the brand of cigarettes he liked in the pocket.

Outside the Imam Ali Mosque in Najaf, we experienced in a microcosm the range of emotions Iraqis felt toward Americans. Young men cursed our team for being infidels, while an elderly man and woman thanked us for coming, and a young girl handed me a piece of fruit.

Although such recollections are unique to Iraq 2003, our field research exemplified larger principles to bear in mind when investigating the humanitarian consequences of war.

First, documentation can make a difference. In 2002, I was part of a Human Rights Watch team that reported on the civilian casualties caused by the US air campaign in Afghanistan from October 2001 to March 2002. We found that the US Air Force’s use of cluster munitions in or near towns and villages killed or injured more than 100 civilians. In Iraq, according to our findings, the US Air Force had learned from its earlier mistakes. It used far fewer cluster munitions in or near populated areas and relied on more accurate models.

US and UK ground forces, by contrast, lacked experience with cluster munitions from Afghanistan and used them widely in major cities of Iraq, causing hundreds of civilian casualties. Pressure from organizations like Human Rights Watch, the results of US military after-action reviews, and the stigma created by the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions (despite the fact the United States has not joined the convention), however, led to a change in practice. Although conflict continued for years after Baghdad fell in April 2003, the United States did not use cluster munitions again there or anywhere, except for an isolated strike in Yemen in 2009.

Second, fact-finding requires careful digging, not quick judgments. For example, we wondered about the pattern of failed US air strikes on Iraqi leaders. The bombs used were precision-guided munitions, but they did not kill any of the intended targets and caused dozens of civilian casualties instead. My colleague figured out that despite the precision of the bombs, the United States determined the location of the targets based on satellite phone intercepts, and those were only accurate within a 100-meter radius.

Our report concluded that it appeared that reliable corroborating intelligence sources were “difficult if not impossible to come by,” leading the United States to “[fall] back upon all it had, namely, inaccurate coordinates based on satellite phones, with no guarantee of the identity of the user.”

Third, field researchers will observe many similarities across armed conflicts. People crave information, for example. In Afghanistan, I saw civilians beat soda cans and other scrap metal into satellite dishes; in Iraq, they purchased dishes. As these cases made clear, those in the midst of conflict will do whatever it takes to get news. While local residents struggle to find out what is going on around them, the international media flocks to the scene to send stories to the rest of the world. Journalists interview and in turn share information with human rights researchers who are documenting violations of international law to promote accountability and improve civilian protection.

Much of the pain war inflicts on civilians is also the same. When used in populated areas, explosive weapons—air-dropped bombs, missiles, rockets, artillery shells, etc.— cause civilian casualties, reduce homes to rubble, and damage infrastructure, which, in turn, interferes with basic services, like health care and education. Cluster munitions can explode on impact or after an attack, leaving civilians without limbs or livelihoods. Parents mourn the loss of their children, and children become orphans.

Fourth, it is our job as researchers and writers not only to identify trends but also to individualize people’s experiences. Putting a human face on armed conflict recognizes the suffering victims have endured and helps make change on their behalf.

Our report on Iraq was about more than the numbers: cluster munitions killed 19 civilians and injured 515 in al-Hilla between March 23 and April 11; the US Air Force targeted 50 Iraqi leaders but killed zero. I sought to relay and still remember the stories behind those figures.

For example, 13-year-old Falah Hassan lost his right hand, his left index finger, and soft tissue in his lower limbs when an unexploded submunition, left by a cluster munition attack, detonated in al-Hilla on March 26. His mother, who lay in the next bed when we visited him the hospital in mid-May, suffered injuries to her abdomen, uterus, and large and small intestines from the same explosion.

An April 8 air strike killed six members of the Jabir family in Baghdad when a bomb intended for Saddam Hussein’s half-brother Watban hit their home. Sa`dun Hassan Salih introduced us to the only survivor, his 4-month-old niece, Dina Jabir. She was miraculously blown out of the house and found the next morning in a neighbor’s garden with broken bones, but alive.

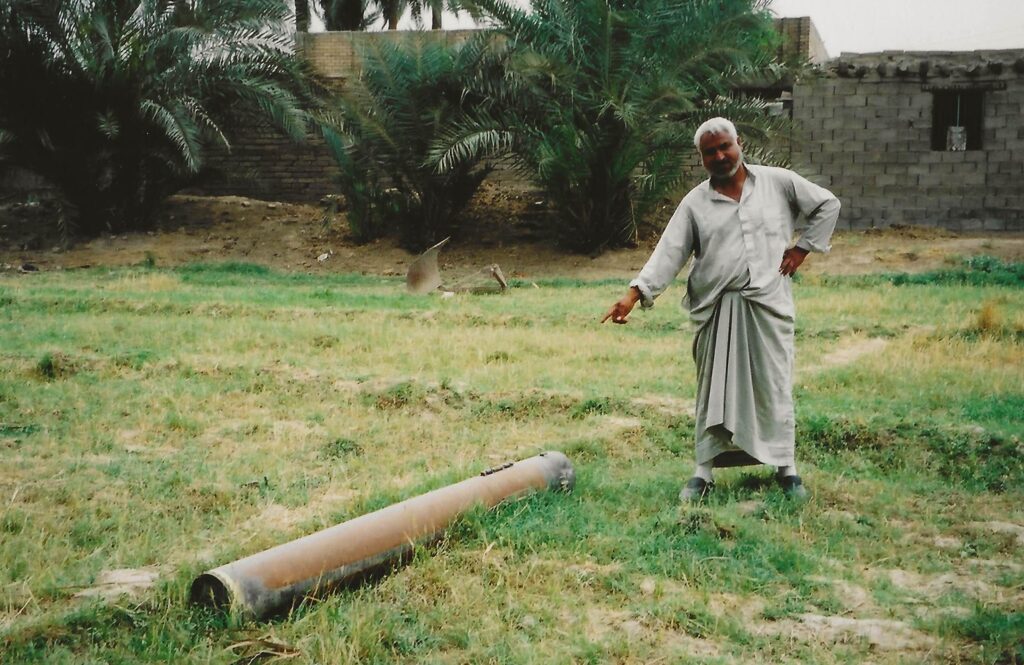

On May 30, our last day in Iraq, residents of Basra showed us live submunitions next to a school and a home before we drove across the border to Kuwait. This unexploded ordnance, and the gunfire we heard while packing our bags the night before, demonstrated that the armed conflict and its impacts on civilians would continue. While we flew home to process our research, our interviewees were left to live with deadly remnants of war and the prospect of resumed fighting.

When I reread my journal two decades later, there were many details I had forgotten, but my conclusions had not changed. My final words in the notebook, which seem to have come true, were: “I felt so close to history and hope our report will lead to some positive change.” Over the past couple of months, journalists and others have looked back on the 2003 US-led coalition’s invasion of Iraq as a historical moment, and our report Off Target contributed to the negotiations of the Convention on Cluster Munitions and changes in US policy.

Today, field research on civilian casualties continues to be needed in the war in Ukraine and other armed conflicts around the world. Although technology has changed and methodology has evolved over the past two decades, the humanitarian purpose and principles of documenting conflict remain the same. In retrospect, our fact-finding trip to Iraq provided both a lesson in history and a guide for increasing civilian protection in the future.

Bonnie Docherty is director of the Armed Conflict and Civilian Protection Initiative at Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic and a senior researcher in the Arms Division at Human Rights Watch.