Building off an inspiring resolution adopted in March 2024 by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, this semester the Clinic’s “Rights at Work” team partnered with the International Lawyers Assisting Workers Network (ILAW) to conduct research on model laws that African states parties could use as they seek to formally account for the work of informal economy workers.

As part of this work, the team traveled to Casablanca, Morocco in early October to attend ILAW’s Global Conference. The third gathering of its type that the network has held since 2019, the global conference brought together members of the international labor law community, enabling the legal experts to share strategies, collaborate on complex cases, and develop context-specific approaches to workers’ rights challenges.

We caught up with Senior Clinical Instructor Aminta Ossom and students Sharif Hamidi ’26 and Chinaza Asiegbu ’25 to learn more about their conference experiences, project objectives, and insights on navigating this influential network of labor rights advocates.

IHRC: Aminta, could you start us off with a brief overview of your current project and introduce us to your partner organization?

Aminta Ossom: Our project was inspired by a resolution that the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights adopted last spring. In March 2024 the African Commission passed a resolution in which they recognized the rights of informal economy workers. In the resolution, the Commission also announced that it would develop guidelines and model laws that states parties to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights could use as they seek to formalize informal economy work legally while also protecting the rights of informal economy workers.

The resolution itself was groundbreaking, and civil society was very excited about it. The majority of workers on the African continent, and actually, the majority of workers in the world, are individuals who work in the informal economy. This is a category of work that includes workers in formal enterprises and workers who work for themselves, who create their own jobs. Often these workers are not provided the same legal and social protection as other workers. So explicitly clarifying that regional human rights law applies to these workers was a breakthrough. The resolution ensures that human rights law is relevant to everyday workers in these contexts.

The work we’re doing in collaboration with the ILAW Network is responding to the Commission’ s call in this area and drawing on the legal expertise of ILAW members to understand what the experience is at the country level, particularly as it pertains to street vendors. With other universities in Africa and the US, we’re also adding academic knowledge to feed into the process to understand how law can shift the experiences of workers in this space.

We were excited that the Commission took this action and built off really positive standard-setting that the African human rights system has already done in this field. We’re looking at ways to practically ensure that the guidance provided is helpful for workers and for African governments.

IHRC: So now let’s turn to one of the students working on the Rights at Work project this semester, Sharif Hamidi. Sharif, this is your first semester in the International Human Rights Clinic – how would you describe your experience joining the project and getting up to speed on the issues? And how did the team prepare for the ILAW Conference?

Sharif Hamidi: As someone who is new to engaging in human rights work, I think it was a very welcome opportunity to make use of the experience and skills that I’ve picked up in other contexts and seeing how that can transfer over to this context. My experience with the Clinic has just been overwhelmingly positive. Everybody has been great to work with. And our partner organization and the folks there are very mission- driven. And that’ s been very nice to experience.

When it came to preparation for the conference, there were a couple of things going through our minds. At least, for me, as an initial matter, I had to figure out working in the international law context, because there’s a different way of doing things than in domestic law. We also did a lot of desk research, making sure we were getting up to speed on the subject matter. And after that desk research, we had reached a point where it felt like we could start to enter these conversations with people in the field.

To prepare for the actual conversations themselves, we started by identifying which questions we wanted to ask that would build off the desk research, what the different pivot points in the conversation could be, and just generally making sure that we were making use of the limited time and opportunity that we had to make sure that our research would be as successful as possible.

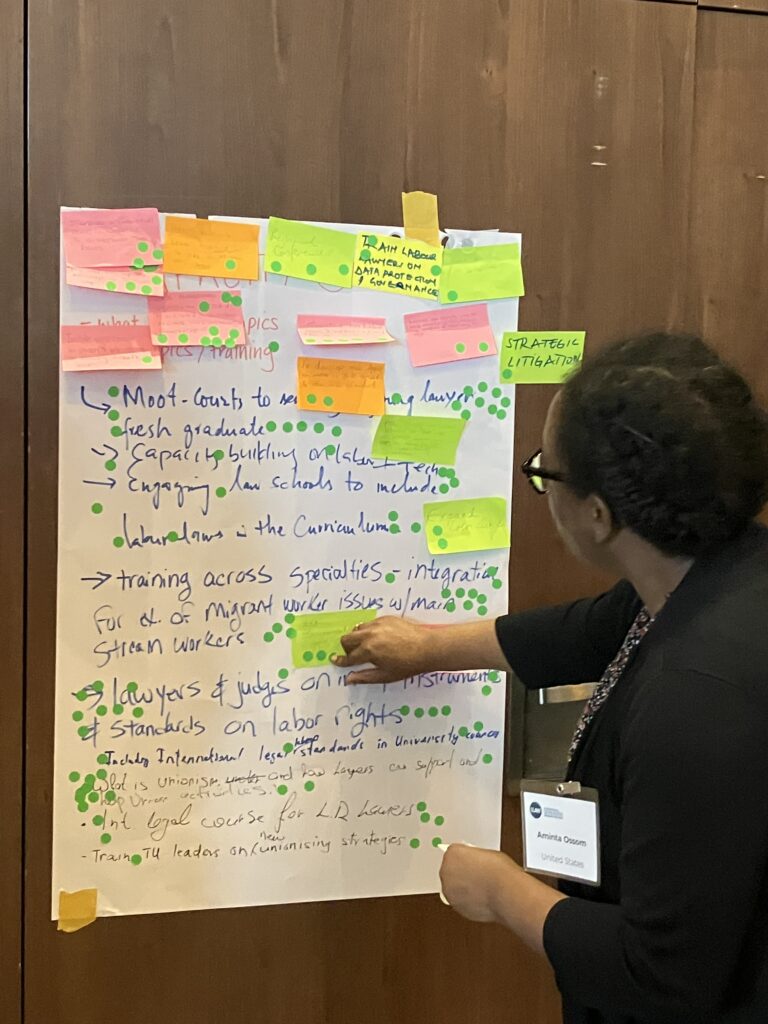

From left to right: Ossom with clinic partners from WIEGO and the Solidarity Center, a brainstorming session at the conference, and the Clinic team signing off during the final day

IHRC: Aminta, can you speak a bit about the specific purposes of the Conference and how this project work fits in?

Ossom: Over the past five years, the ILAW Network has been convening gatherings in different regions of the world where lawyers who work in this area can come together and share approaches and learn from each other. The ILAW membership is involved in public education, internal peer-to- peer education, and different law reform processes so the meeting was a chance to learn about all this work and to share experiences.

When we went to the conference, we were hoping to learn from the discussions that were had there, and at the same time, understand specifically from lawyers who work in different African countries the role that the law plays in the lives of informal economy workers and street vendors in particular. What could legal guidelines and model laws actually do to better protect the rights of these workers?

We also had discussions with lawyers working in jurisdictions where laws had already been passed related to street vendors, to understand what the implementation of those laws has looked like. Are there obstacles to implementation that could be addressed at the legal drafting stage? Are there questions that we haven’t thought of that we should be thinking of? And how should that direct our desk-based research and framing documents that the ILAW Network and allies could use when seeking the views of vendors and others on potential model laws?

IHRC: For both of you, what was it like to interact with the various partners and ILAW Network members? What were some of your impressions or key takeaways?

Hamidi: Our conversations with the folks at the conference were very illuminating. No matter who we spoke to, the person on the other side of the table was always someone who was very knowledgeable and cared deeply about the work they were doing. It was great to be in an environment where people have such passion and expertise for the work, and it was also very helpful from a project perspective as well.

Before we arrived, we had learned about the range of types of interviews and did a lot of practice. We discussed how to tailor the conversation for somebody who is a subject matter expert and how that differs from interviewing someone living the reality of being a street vendor or a member of the informal economy.

What we found is that there was a sort of creative quality to the conversations we were having. As the conference wore on and we had more conversations, we would reach these conceptual breakthroughs, where suddenly, things that we had discussed in earlier conversations suddenly made a lot more sense in light of the later ones we were having.

We were frequently having conversations during lunch or the afternoon tea break or in a hallway somewhere. And so, there was a little bit of juggling that needed to be done. For example, sometimes we were trying to conduct an interview during the lunch break and have that conversation at a table where there would be many other people, including the person we’d requested the interview with. And what ended up happening- and being quite helpful – was that different folks at the table would get inspired by each other’s contributions and they’ d start bouncing off each other. And you’re suddenly pulling this conversational thread that’s become much richer by the contributions of everybody else who’ s there.

Chinaza Asiegbu: As the conference went on, we continued to develop our knowledge, and even shift the direction of the kinds of questions we were asking based on how things evolved. We started with our initial set of questions but allowed flexibility for people we were meeting to also drive the conversations and let new questions emerge.

I think it’s important to remember that even when you’ve read a lot on an issue and have your own idea of how things “should be”, you should always remain open to those ideas being disrupted by facts on the ground.

IHRC: What skills did you find most valuable when navigating the Network and conference environment?

Asiegbu: One of the key aspects of the trip that I think was really valuable was the ability to enrich yourself in an environment. And even though we had a few weeks in the Clinic to learn how to fact find and learn the terrain of informal work in human rights law, I think that being at the conference was still completely a change. Having conversations with a lot of experts in the field – people who have devoted their entire career to working with informal workers and people who have represented their individual communities- it felt like we were in this new world.

When I first got there, I was a bit intimidated by what that would look like. I wondered: how do we have real conversations with people who are such experts? One way I think that I successfully overcame that was just to get to know people outside of the aims of the conference, asking them, “What are your interests?”

And people at the conference took us under their wing. They were not only invested in our contributions and the goals of our project but also our interests as students. The participants would ask, “Why are you interested in this project and Africa? What are your interests in labor law? Do you want to be a labor lawyer?” In fact, they had their own aims too – maybe convincing us that labor law is the place to be! So it was interesting and really fun for me and Sharif to navigate this opportunity and get to know all of these professionals. And surprisingly, a lot of our interviews emerged from those networking encounters.

IHRC: Any lasting impressions from your time in Morocco? Did the experience change your perspective on your work in the Clinic or human rights advocacy generally?

Hamidi: I think for me, the big takeaway is humility. Especially because we had originally divided our project into two parts: a research phase and then a drafting phase. This conference came towards the final third of our research phase. By the time we arrived in Morocco, it felt like we had developed a decent understanding from desk research of what the broader context was, both in terms of the law and some of the facts just from reviewing legal materials and news articles and seeing what’s out there in the public domain. I learned that there’s so much that gets lost in between what happens in the real world and what makes its way into these written materials.

I had a theoretical understanding, my practical understanding is still being built out. And that practical understanding is significantly more consequential, I think, especially to a drafting process. The theory gives you the framing, but the practical understanding is what really gives you the, the sort of nuts and bolts that will go into the final product.

Asiegbu: One thing that I’m learning throughout this experience is that things can’t always be put into neat boxes. Even if those boxes were developed to try to encompass the complexity of some of the problems that we’re confronting, your categorizations shouldn’t be limiting.

For example, when we were trying to articulate things in human rights terms or in the human rights framework, we were constantly running into the interdisciplinary nature of the work. We were regularly asking ourselves, “Oh, is this a human rights question actually, or is this an urban planning question? Is this something for us to even be interacting with?”

Trying to think about what rights and entitlements really mean – in the process, you interact with business and economics and law, and urban planning, and politics – these things are all so intertwined. And I think that that has been a challenge. When that happens, I think that there’s a temptation to say “this mandate or this project isn’t enough.” You can be tempted to say, “We need to do more, and we need to be involved in all these other buckets to truly create the change we want to see.” But I think it’s a real skill to be keen to the nuances and opportunities within a human rights mandate. There’ s always going to be parameters, but there are also opportunities within those parameters to expand opportunity and create more value for others.

Ossom: For me personally, I was inspired by the fact that the conference was both reflective and forward-looking. At the beginning of the conference there was a really powerful introduction to our hosts by the head of the Solidarity Center, the organization that launched the network. The director was describing the history of the Arab Spring as connected to the concerns of a Tunisian street vendor, a person in despair about having a lack of livelihood. It was really powerful to understand labor and human rights as connected to North African history in particular, and it was a really moving way of tying the place where we were to the goals of the conference and the work of all those attending.

I was also personally influenced by the atmosphere of the conference, which was both robust and realistic about the challenges that are out there in the human rights and labor rights fields. It was encouraging to hear about the activities of the ILAW Network and the different legal strategies that have been influential to better protect the rights of workers in different contexts. Our project is a small piece of that work being carried out worldwide. It was encouraging to know that the collaboration we undertake with like-minded lawyers can really make a difference.