Investing in expanded water services could improve the situation for women and underserved communities, according to a report from Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic and the Center for Economic and Social Rights

Low-income residents of Delhi suffer from unequal access to water – and inaction by governments, coupled with climate change, is likely to make the situation even more dire for millions of people. That is the conclusion reached by a new report released by Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC), in conjunction with the Center for Economic and Social Rights (CESR).

“Our report shows that, without urgent government action, millions of Delhi residents could lack consistent access to clean water in the very near future,” said Aminta Ossom, the IHRC instructor who supervised research for the report. “Inaction in this context threatens the right to water, which is guaranteed under international human rights law.”

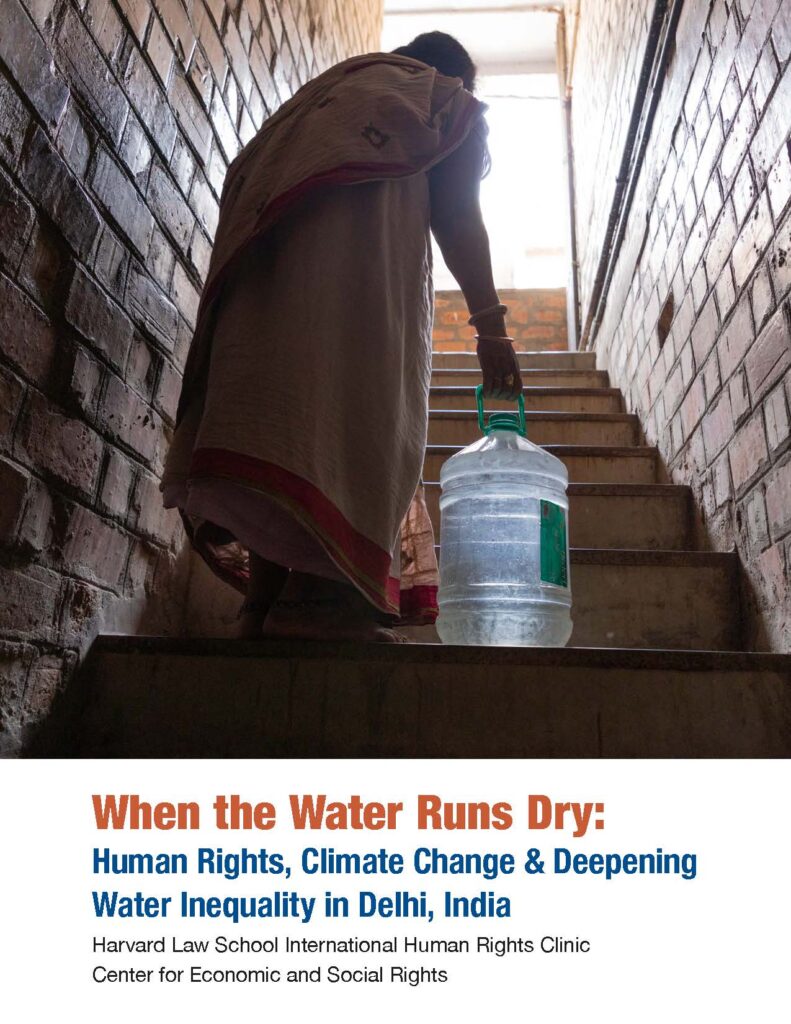

Because Delhi does not generally extend water pipelines to homes in the city’s growing number of unplanned communities, poor residents – and low-income women in particular – face mounting barriers to collecting and storing water, even as India contends with increasing heat, finds the report, which was released during the UN Climate Ambition Summit.

The Delhi water authority delivers water to the city’s unplanned colonies by community taps, tanker trucks, or wells, all of which provide smaller amounts of water on a more irregular basis than the in-home taps present in wealthier areas. This system means that low-income residents often travel long distances and wait longer to acquire water during limited distribution times. They also devote a significantly higher portion of their income – around 15 percent – to obtaining, treating, and storing water, according to estimates included in the report.

“The decision not to extend water pipelines to homes in Delhi’s unplanned colonies is a consequential one,” Ossom said. “Low-income residents of the city, who reside in those areas, end up depending on more precarious water delivery systems. Our report shows that climate change puts those systems under intense pressure.”

The report also concludes that climate change amplifies the inequality that the communities face by reducing and worsening their water supply. Areas with already limited water availability are more affected by water scarcity. Temperature spikes heighten the demand for water while increasing the physical stressors of collecting it. Higher temperatures also reduce the amount of oxygen that water holds, which affects its taste, odor, and appearance, while floods from high-intensity storms degrade water sources.

Inaction has gendered impacts, the report shows. “Women and girls are the ones tasked with collecting water for their families,” said Alina Saba, a climate justice campaigner with CESR. “They will have to spend even more hours each day collecting water, which steals time from their educational and income-generating activities, increases the burden of their care work, and has consequent impacts on their human rights to education and sanitation.”

The report suggests measures that the Government of India and the Delhi government could take to protect the right to water. “One way to improve the situation would be to increase resources for water service delivery by raising tax and non-tax revenue streams,” said Ossom. “Expanding the water supply for unconnected households and monitoring water delivery in a disaggregated fashion would also help reduce inequality.”

The authors do not let wealthy governments off the hook. “Wealthy countries that have contributed the most to historical greenhouse gas emissions have skirted their responsibility to finance climate action,” said Saba. “They should deliver on their commitments by providing the 100 billion dollars a year that they promised a decade ago to developing countries and rapidly increase climate funding. At the upcoming UN Climate Change Conference, governments should agree on a transparent and equitable structure for the Loss and Damage Fund,” she said.

Harvard Law students followed an innovative method designed by CESR, called OPERA, when conducting research for the report. The approach aims to reveal seemingly invisible policy choices that contribute to socio-economic inequality, resulting in economic and social deprivations. The report draws from 200 written sources in addition to interviews with subject-matter experts and community representatives.